New press release live from UNOC: Read here

Investing in mangroves is one of the most powerful and cost-effective ways to deliver simultaneous gains in climate mitigation, resilience, biodiversity, and livelihoods.Unlocking their full value will require financing models that go beyond carbon – recognizing mangroves as high-performing natural infrastructure with multiple benefits.Protecting and restoring mangroves will have replicating benefits for ecosystems in the seascape, such as coral reefs, seagrasses, salt marshes and mud flats.

Mangroves are a collection of approximately 80 different species of trees or large shrubs that grow in coastal areas in tropical and subtropical climates. They are halophytes, which means they are salt-tolerant plants. They grow particularly well in brackish water, where saltwater and freshwater bodies meet, and where the sediment has a high mud content. Mangroves’ tangled roots grow above and below ground, forming dense thickets that are home to a huge variety of plants and animals.

Mangrove soils are permanently waterlogged, poor in oxygen, and have constantly changing salinities due to being alternately submerged and exposed to the air as the tide rises and falls. These anaerobic conditions and slow decomposition are also what makes mangrove forests such effective carbon sinks. Sequestering carbon at up to four times the rate of terrestrial forests and storing carbon not only in their biomass but also in their soil and sediments, mangroves are among the most effective carbon sinks on earth.

Mangrove forests cover just 0.1% of the planet’s land surface. Yet these ‘blue forests’, found along the coasts of tropical and subtropical regions, provide vital ecosystem services to people and planet. They offer a haven for biodiversity, help maintain the climatic conditions that sustain life on earth, and provide protection, food, and livelihoods to coastal communities.

For many coastal communities, mangroves are the first line of defence against floods, storms, and erosion, protecting lives and property. Mangroves also are a critical source of food security for communities, and provide alternative livelihood opportunities through natural resources, including timber, fuelwood, honey, and traditional medicines. Mangrove tourism is estimated to represent a multi-billion dollar industry, attracting tens to hundreds of millions of visitors annually and offering unique cultural significance as spiritual sites, scenic and therapeutic destinations.

Mangroves are home to 341 threatened species and serve as vital habitats for wildlife on land and sea. From Bengal tigers and monkeys to turtles, dolphins, and dugongs, these ecosystems support nesting, breeding, and feeding across the food chain. They also filter water and cycle nutrients, sustaining nearby coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and the broader coastal web of life.

The world is waking up to the need to secure the future of this extraordinarily valuable ecosystem. Defining the business models to unlock capital for these ecosystems will be critical to harnessing this momentum.

The largest area is in Indonesia, where mangrove trees cover almost 3 million hectares (30,000 km2), about 20% of the world’s total, followed by Brazil, Australia, Mexico, and Nigeria.

For near real-time data on global mangroves, visit Global Mangrove Watch—a free, accessible platform for maps and monitoring used by policymakers, investors, researchers, and conservationists.

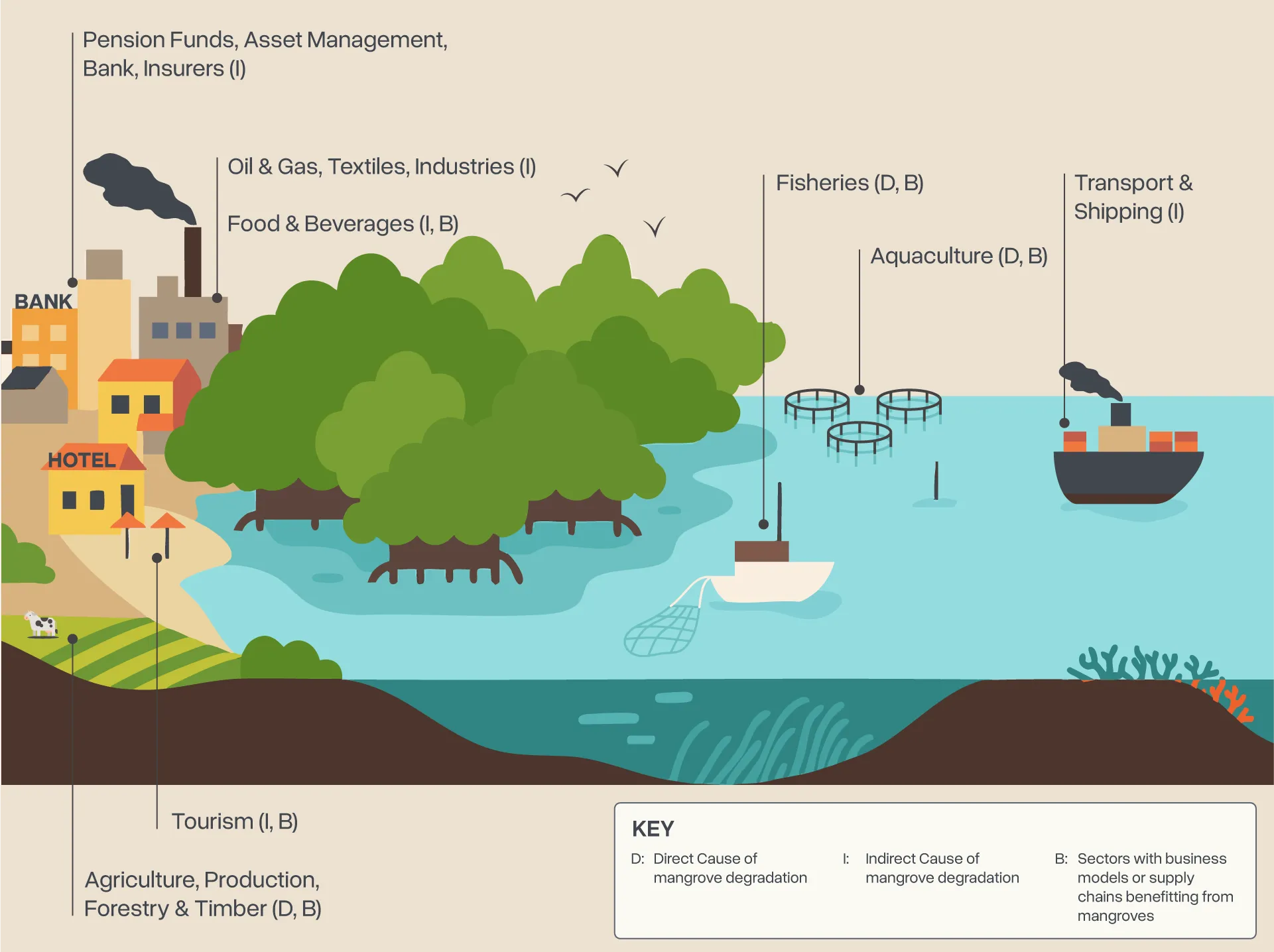

This is largely driven by degradation linked to commodities like shrimp and palm oil, infrastructure expansion, illegal deforestation, and pollution. Fortunately, rates of loss have slowed substantially, with average annual net losses over the last decade of 6,600 hectares (66km2) or 0.04% of all mangroves. This decreasing rate of loss is mostly due to increased protection, changing industrial practices, expansion of rehabilitation and restoration, and stronger recognition of the ecosystem services provided by mangroves.

Mangroves remain at risk, threatened by a combination of direct human impacts, such as clearance and conversion, as well as by natural and climate change-induced biophysical impacts. While natural gains or large-scale rehabilitation have increased mangrove coverage in some parts of the world, other areas, such as Southeast Asia, are experiencing massive loss of old-growth mangroves. Over 60% of losses since 2000 were due to direct human impacts. Events such as erosion, rising sea levels, storms and droughts are also causing significant loss of mangroves, and are further exacerbated by climate change and other human impacts.

The planet is in the grip of a polycrisis, facing climate breakdown, biodiversity loss, growing food insecurity, and mounting geopolitical instability. Now, more than ever, we cannot afford to lose mangroves.

The case for action to protect, restore and secure the future of these crucial ecosystems is clear. But to make this possible, investment at scale is urgently needed, as is effective, multi-stakeholder collaboration.